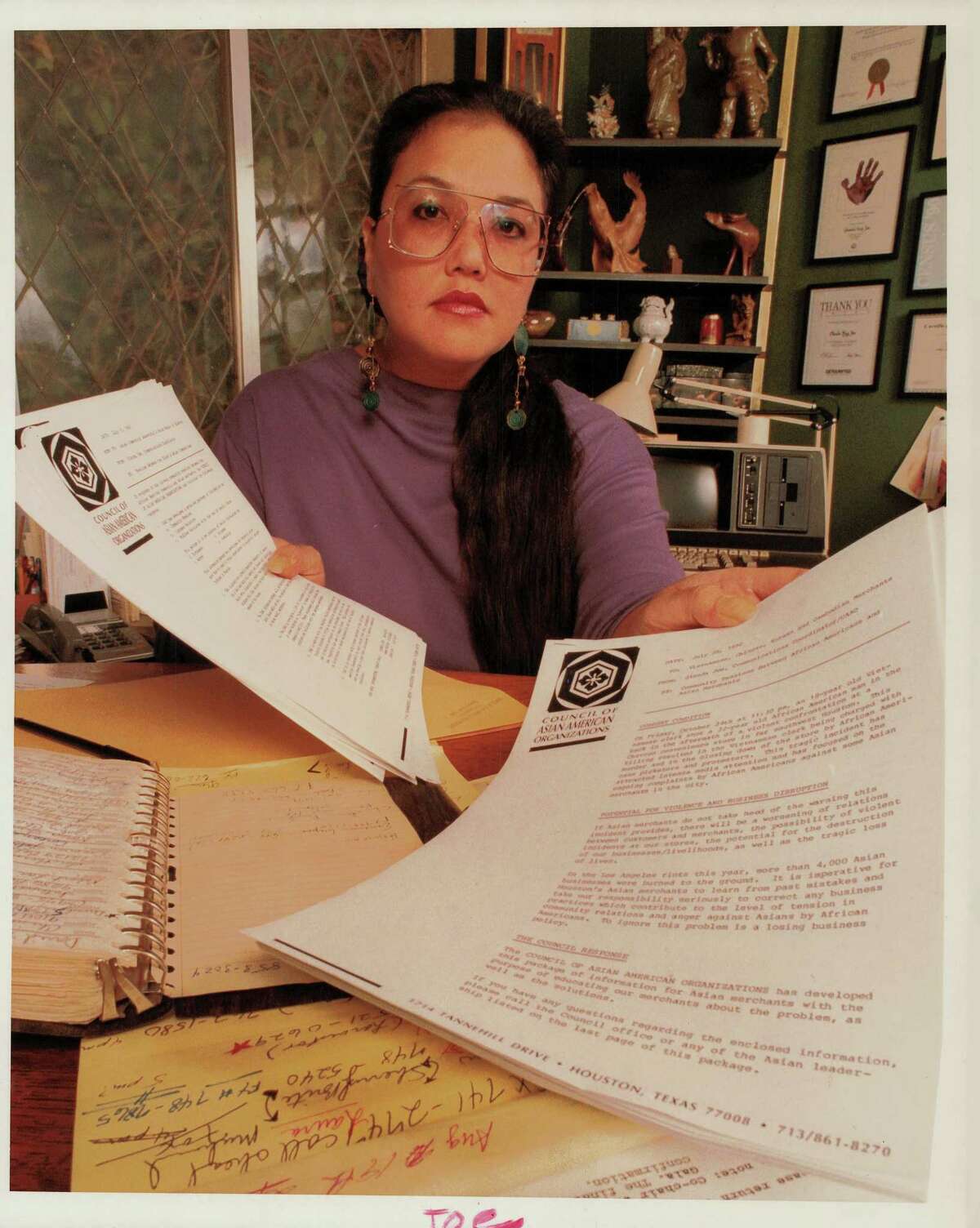

Glenda Joe was born in Houston in 1952, the daughter of a Chinese father and a white mother.

When her parents were married, the U.S. Supreme Court was still over a decade away from declaring interracial marriage a constitutional right.

“For the longest time, when we drove around town and we saw another Asian in the car, we would stop and point,” she said. “I never looked like anybody else.”

CENSUS DATA: How Houston's Asian community has exploded in growth and diversity since 1869

Over 70 years later, Texas has the largest concentration of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the South, and the Houston metro area has the one of the top ten largest Asian American populations in the United States, according to 2020 census data.

Houston is home to first to fifth generation immigrants, from Sri Lanka to South Korea and Pakistan to the Philippines. For Asian American and Pacific Islander History Month, the Houston Chronicle spoke to Houstonians about their immigration stories and what makes Houston feel like home.

“The Asian community, Pacific Islanders to South Asians, are so much better at becoming Houstonians than someone who lives in St. Louis,” Joe said. “And the reason is because families help each other.”

The first Asian immigrants

The way Glenda Joe tells it, the first Chinese person to arrive in Houston was her ancestor Jim Joe, who came in the early 1880s searching specifically for a city where there wasn’t already a large Chinese population.

Jim Joe was on the run after getting in trouble with Boston’s Chinese community, she said, and found himself in Houston, then a city of less than 30,000.

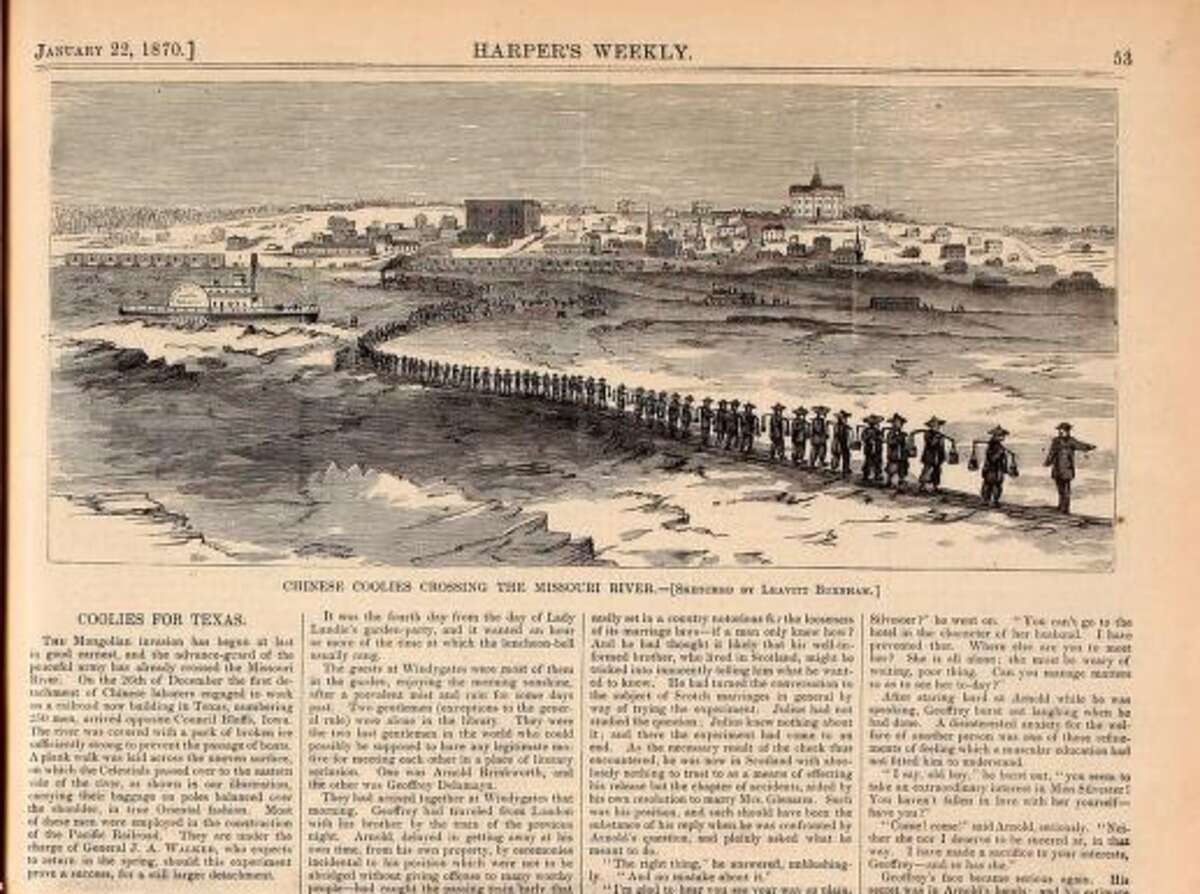

Chinese immigrants like Jim Joe were the first group of Asian immigrants to come to Texas in large numbers, according to Anne Chao, adjunct lecturer at Rice University and program manager of the Houston Asian American Archive. At first, they were seen as a cheap source of labor for working on railroads and farms following the abolishment of slavery in the United States. But over time, white Americans came to see them as competition for jobs, Chao said.

So in 1875, Congress began limiting Chinese immigration, first through the Page Act and then the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, banning nearly all Chinese immigration into the U.S.

REPORTER'S NOTEBOOK: Tracing the history of AAPI migration to Houston

This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

Still many immigrants made their way to the U.S. as “paper sons” ― Chinese immigrants presenting documents, often fraudulent, that identified them as born in the U.S. or the child of someone born in the U.S.

Glenda Joe’s father came to the country in 1930 as a paper son. He was 8 years old when he arrived in Angel Island Immigration Station in the San Francisco Bay and made the journey to Houston. In Guangzhou, her family’s last name was most likely spelled Cho or maybe Chao ― in America, they became Joe. Her father, Tong Bin, became Lawrence.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943 following China’s alignment with the Allies in World War II, and the U.S. made slow strides toward allowing other Asian immigrants in as well.

But discrimination against Asian Americans persisted. When Joe was 8, she remembers landowners refused to sell her parents a house once they found out her white mother had a Chinese husband. In 1981, the Ku Klux Klan harassed Vietnamese shrimpers in Seabrook. Joe, then in her late 20s, got in her car, drove to the police station and offered to help.

“I sat across from the Grand Dragon of the Klan in Seabrook and made him feel comfortable because I talk like him,” she said. “My Southern accent reinforced familiarity in his head while we were talking about stuff he thought of as foreign and alien. It was amazing.”

JAPANESE IMMIGRATION: Inside the history of Texas' first Japanese immigrants who built the state's rice industry

Since then, Joe has watched Houston’s Asian population grow and diversify. When Vietnamese, Japanese and Korean immigrants first came, they taught art and dance in schools to keep their culture alive. But the schools faded away as the teachers who taught there aged, she said.

So Joe began running the Houston Asian American Festival, now known as Lunar New Year Houston, a pan-Asian festival that brings together Houstonians from different cultures to celebrate the shared Lunar New Year holiday. This year marked the 14th year of the festival.

“The one cultural preservation that I knew would live on past me was the Lunar New Year Festival,” she said. “Since we created a free annual cultural event that would promote lion dancing, we’ve seen a blossoming number of lion dance groups, Chinese and Vietnamese, so we’re keeping the culture.”

The opportunity for education and jobs

Kazi Salman Jalali likes to say he came to the U.S. with $400, four children and four suitcases.

Living in Pakistan in the 1960s, many of his classmates left to study in the U.S. In 1965, Congress had passed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, removing restrictive immigration quotas and creating new opportunities for highly skilled immigrants and relatives of U.S. residents to immigrate. The law “opened the door” to south Asian immigration in particular, according to Anne Chao.

Jalali immigrated in 1979 after securing sponsorship from his brother-in-law. Jalali, then living in Saudi Arabia, first moved to Miami with his wife, Farzana, and their children. The family came to Houston in 1983. Giving his children access to quality higher education opportunities was top of mind.

Over the past four decades, Jalali has observed many immigrants come for their careers, especially to work as engineers or doctors, or to run businesses — in his words, for “good living.”

“You can get a job. You can have your own business,” Jalali said. “And the air is pure. The food is pure. The quality of life is good.”

Mohammad Faruque and his family immigrated to the U.S. from Bangladesh in 1977 when he was 1 year old. His father, a geologist, moved the family to Houston for a job in the oil and gas industry.

Faruque remembers Bangladeshi community members would rent out space at the University of Houston for major cultural events, giving families a chance to meet up and spend time together.

Now, Faruque and his wife, Silvia, are the ones helping organize Bengali cultural events to foster a connection to arts and culture.

Businesses foster community

Two years before Faruque’s family made it to Houston, Anna Pham’s grandparents arrived in the U.S., seeking a home free from violence.

The Vietnam War ended in April 1975, and by June, the first Vietnamese refugees were in Houston. Pham’s family immigrated in 1975 to South Dakota, where they had secured sponsorship from a local family. About three winters later, they’d had enough of the snow and cold, Pham said. The humidity of Houston, similar to the tropical climate of Vietnam, felt like a better fit for Pham’s grandparents and their eight children.

Pham’s grandfather had been a hunter and a fisherman in Vietnam, and her grandmother was a food vendor in a market. Neither knew how to read in Vietnamese, let alone English. They opened a pool house with a buffet, but quickly realized that more people came for the food than the pool.

That pool house became Mai’s Restaurant, named after Pham’s mother, who her grandparents felt like had the easiest name for Americans to pronounce.

Pham works as the general manager, on top of attending law school, and still gets customers who mistake her for her mother. Two of her children are the fourth generation of her family to work at the restaurant.

When Mai’s opened, Houston’s main Chinatown was still located in EaDo, and Midtown was still an epicenter of Vietnamese businesses.

“(My grandfather) would love to go walk a couple blocks down to the grocery store or grab something,” Pham said. “It felt just like he was in Vietnam for a good half a mile.”

VIDEO: Mai's Restaurant is a late-night, Vietnamese comfort food haven for Houstonians

Now Playing:

Kenenth Wu arrived in Houston in 1980, just in time to watch as the new Asiatown on Bellaire Boulevard flourished.

He came from Taiwan to study at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque in 1973, and then lived in New York City, where he met his wife.

But like Pham’s family, shoveling snow felt foreign to Wu and his wife, May, who had both grown up in the warm climate of Taiwan. In 1979, he came to Houston on a business trip, and one year later, he and his wife moved.

Wu opened a trading company and motel.

Golden Bank, then known as Texas First International Bank, supported small business owners like Wu. The bank was located on Bellaire in 1985, in the middle of the newly developing Asiatown, to give new immigrants the opportunity to bank in their native language, often with people who themselves had immigrated.

Wu began working there in 1991. At the time, he estimates over half of the bank’s customers were local Taiwanese-owned businesses.

Now it’s more like 5 to 10 percent of their Texas business, Wu, who is now chairman, estimates. The children of the immigrants of the ‘80s can easily bank at bigger, English-speaking banks, and many are doctors and lawyers instead of restaurant or grocery store owners, he said.

Wu, now 75, goes to the community center every holiday and makes donations to the center and local cultural associations. It’s his way of giving back to the community that supported him when he first came to Houston.

“Us Taiwanese Americans, I think we should contribute back if we benefited from the community,” Wu said. “We need to try to help the second generation, or even the younger people, one day, to start their own business."

Kenneth Wu (left), chairman of Golden Bank, and Anna Pham (right), general manager of Mai’s Restaurant, pose for photographs. (Yi-Chin Lee/Staff photographer)

Life in the suburbs

Suren Lewkebandara and his family found “home” at the Houston Buddhist Vihara.

Lewkebandara moved to the United States from Sri Lanka in 1989 with his wife, Asanka, to pursue his Ph.D. in chemistry at Wayne State University in Detroit.

He had heard of Texas as a boy — his father used to read Western novels, and growing up, Lewkebandara jokes, the books were how he learned English. When Lewkebandara got a job offer at a chemical manufacturing company after graduating, he, his wife and their two small children made their way to Clear Lake.

At the time, he recalled there were about 150 Sri Lankan families in the Houston area, the first of whom had arrived perhaps 30 years before. Many of them were like the Lewkebandaras — professionals with young families, and the Vihara became a center of community life as well as religious instruction.

“That was our meeting place on Sunday. You get to get together, have our sermons and everything, and then we’d have potlucks. It’s just like you are back in Sri Lanka,” Lewkebandara said. “The kids had their friends, and there was room; they could run around playing soccer.”

The temple grew with the Sri Lankan community, and began offering language classes, dancing classes, and music lessons, which Lewkebandara now teaches. The Clear Lake community grew too, along with Friendswood, where the Lewkebandaras now live.

When he goes to the grocery store, he’s greeted by everyone — a tell-tale sign of a tight knit community, Lewkebandara said.

As the suburbs surrounding Houston developed, more immigrants also made their home there. Matt Manalo, 38, moved from Manila to Alief in 2004 with his parents after his mother got a job as a teacher at a charter school.

SUBURBAN LIFE: Asian Americans are the fastest growing demographic in Houston's suburbs. Here's why.

Matt Manalo talks about the community loom at the Alief Art House on Jan. 13, 2022, in Houston. Manalo immigrated from Manila in 2004 with his parents.

Melissa Phillip, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographerHis maternal grandmother and several relatives were already in the Houston area, he explains. They’d been in Houston for his grandfather to receive cancer treatment before his death in 2002.

The transition to Houston was difficult for Manalo’s father, who had worked for an electrical company in the Philippines and found himself feeling a bit untethered after arriving in Texas.

But at 19, Manalo felt comfortable in the neighborhood, which included Filipino neighbors as well as relatives, and a nearby Catholic church that counted many Filipino, Vietnamese and Nigerian families among its parishioners.

“I thought it was a blessing that we moved to Alief because I didn't feel like an outsider that much,” Manalo said.

And he’s looked to contribute to that community, too. Growing up in Manila, being an artist never felt like an option, Manalo said, but two years after arriving in Houston, he began studying art at the University of Houston.

In 2019, Manalo launched the Alief Art House and Filipinx Artists of Houston, a collective that includes some 40 Filipino artists, supporting each other’s professional pursuits as well as younger artists in the community.

His travels around the country to cities such as New York and Chicago have reinforced his impression that the sense of collective purpose and collaboration he found in Houston is distinctive.

“We have amazing folks who are here and help build the city together,” Manalo said.

Pacific Islanders community grows

Jacqueline Ka’ulaokeahi Kaleo Cline is not technically an immigrant — like much of Houston’s Pacific Islander community, she was born and raised in Hawaii. She came to Houston in 1994 to be with family and work in the aviation industry.

Cline, 60, is one of only 690 Hawaiians in Harris County in 2020, according to the Census Bureau. But the community is growing — something Cline’s observed firsthand as moderator of one of Houston’s largest Facebook groups for Hawaiian Islanders. Since 2020, she’s seen the soaring cost of living in Hawaii drive many to the relatively affordable Houston.

But even without a large Pacific Islander population, Cline still makes Houston feel like home. She travels locally and around the state for cultural festivals and finds Hawaiian papayas and Aloha-brand shoyu at local Asian grocery stores. In the Facebook group she moderates, people drop invitations to have a potluck, share music or do crafts.

Just like Glenda Joe in the 1950s and ‘60s, when Cline drives through Houston, she keeps an eye out for people who look like her.

“We’re always looking out for each other and helping each other,” she said. “If you drive past someone and see they’ve got up some type of Hawaii sticker, we’re doing the shaka sign at each other as we’re driving down the road.”

Sam Gonzalez Kelly, Fatima Farha and Cat DeLaura contributed to this story.

megan.munce@chron.com

nusaiba.mizan@houstonchronicle.com

erica.grieder@houstonchronicle.com

"asian" - Google News

May 18, 2023 at 06:07PM

https://ift.tt/twNYZgP

Why are there so many Asian Americans in Houston? - Houston Chronicle

"asian" - Google News

https://ift.tt/uyCT8R9

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

No comments:

Post a Comment